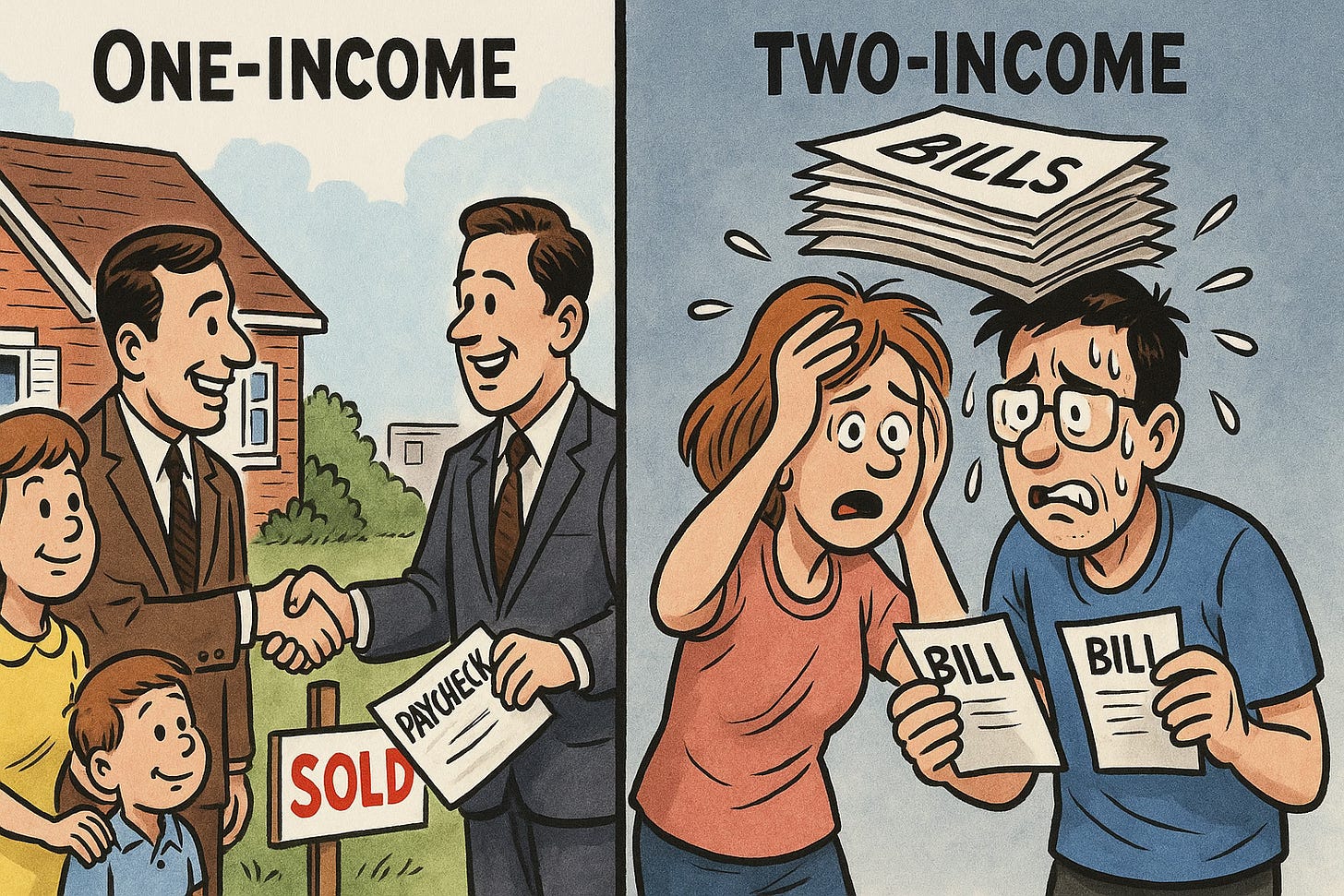

When Two Paychecks Aren’t Enough

one paycheck is used to support a family

Not long ago, the idea that a single income could support a family, buy a home, and still leave room for savings was not a fantasy but an everyday reality for millions of Americans. Today, the notion seems almost quaint. Families with both parents working full-time still find themselves struggling to cover mortgage payments, childcare, and basic expenses. The question is not whether this change has occurred but why.

The answer lies in a mix of economic realities, political decisions, and cultural changes that have steadily eroded the purchasing power of ordinary Americans. What families once managed with one paycheck now takes two, and even then, homeownership often seems out of reach.

The most obvious culprit is housing itself. For much of the 20th century, homes were built in response to demand. Zoning laws were modest, regulations limited, and developers could build subdivisions that met the needs of working-class families. The result was a supply of homes at prices consistent with a single breadwinner’s salary.

Today, by contrast, restrictive zoning, endless permitting delays, environmental impact reviews, and urban growth boundaries have artificially limited the supply of housing. Politicians speak endlessly of “affordable housing,” but their policies often ensure the opposite. Scarcity drives prices upward, and what was once within reach of a factory worker’s paycheck now requires the combined incomes of two college graduates.

Compounding this is the erosion of the dollar. A home that cost $30,000 in 1970 might sell for $300,000 today. While wages have risen in nominal terms, they have not kept pace with the costs of housing, healthcare, and education—three sectors heavily influenced by government subsidies and regulations.

Inflation, often dismissed as a mere statistic, has real-world consequences. It punishes savers, rewards debtors, and quietly transfers wealth from families to government through devalued dollars. The Federal Reserve’s willingness to inflate the currency may ease government borrowing, but it does so at the expense of the family trying to buy a modest home.

The rise of two-income households has also fed a vicious cycle of higher taxes and spending. In the 1950s and 1960s, when most families lived on one paycheck, tax burdens were lower, and government played a smaller role in daily life. As more women entered the workforce, household incomes rose—and with them, so did government appetites for revenue.

Today, payroll taxes, income taxes, property taxes, and countless hidden levies consume a far greater share of family earnings. Parents working two jobs may feel more prosperous, but much of their extra income flows directly into state and federal coffers, leaving them little better off than their single-income predecessors.

Equally important is the shift in cultural expectations. Families of earlier generations lived with fewer material luxuries. Homes were smaller, cars simpler, and consumer credit less accessible.

Today, the average home is larger, the average car more sophisticated, and the average household more indebted. While these changes may seem like progress, they mask the fact that families are working harder simply to stand still. What looks like greater abundance is often just greater financing.

Another overlooked factor is the hidden cost of two-income households: childcare. When one parent stayed home, children were raised within the family unit at no monetary cost. Now, with both parents working, childcare expenses eat up a large share of the second income. For many families, the financial gain of a second job is largely offset by the costs it creates—daycare, commuting, professional wardrobes, and meals eaten outside the home.

The irony is that what once looked like liberation often turns into a treadmill. Families must work longer hours, pay more taxes, and spend more just to replace the functions once performed within the household itself.

Government policies have exacerbated the problem at every turn. Subsidies for housing—like Section 8— inflate prices rather than reduce them. Student loans drive up the cost of education, saddling young couples with debt before they ever buy a home. Healthcare regulations drive up insurance premiums and medical costs, leaving less income for mortgages or savings. Each intervention is sold as “help,” yet the cumulative effect is to raise costs and erode the independence of families.

The decline of the one-income household is not a mystery, nor is it inevitable. It is the predictable outcome of policies that inflate currency, restrict housing supply, tax incomes heavily, and subsidize inefficiency. At the same time, cultural changes have encouraged families to trade stability for consumption, and responsibility for dependency.

The lesson, as always, is that trade-offs cannot be wished away. The decision to regulate, subsidize, or inflate has consequences, and those consequences often fall hardest on ordinary families. Where once a single income bought a home and raised a family, now even two incomes often fail to keep pace.

The American Dream of homeownership and stability was once built on the foundation of liberty, thrift, and opportunity. Families were not richer in the material sense, but they were freer from crushing debt, from overbearing regulations, and from the silent theft of inflation.

Today, that dream is eroded not by fate but by design. The policies of politicians, the incentives of bureaucracies, and the illusions of consumer culture have all combined to make the ordinary struggle harder. If America wishes to restore the possibility of the one-income household, it will require more than nostalgia. It will require a sober recognition of how far we have strayed from the principles that made prosperity possible in the first place.