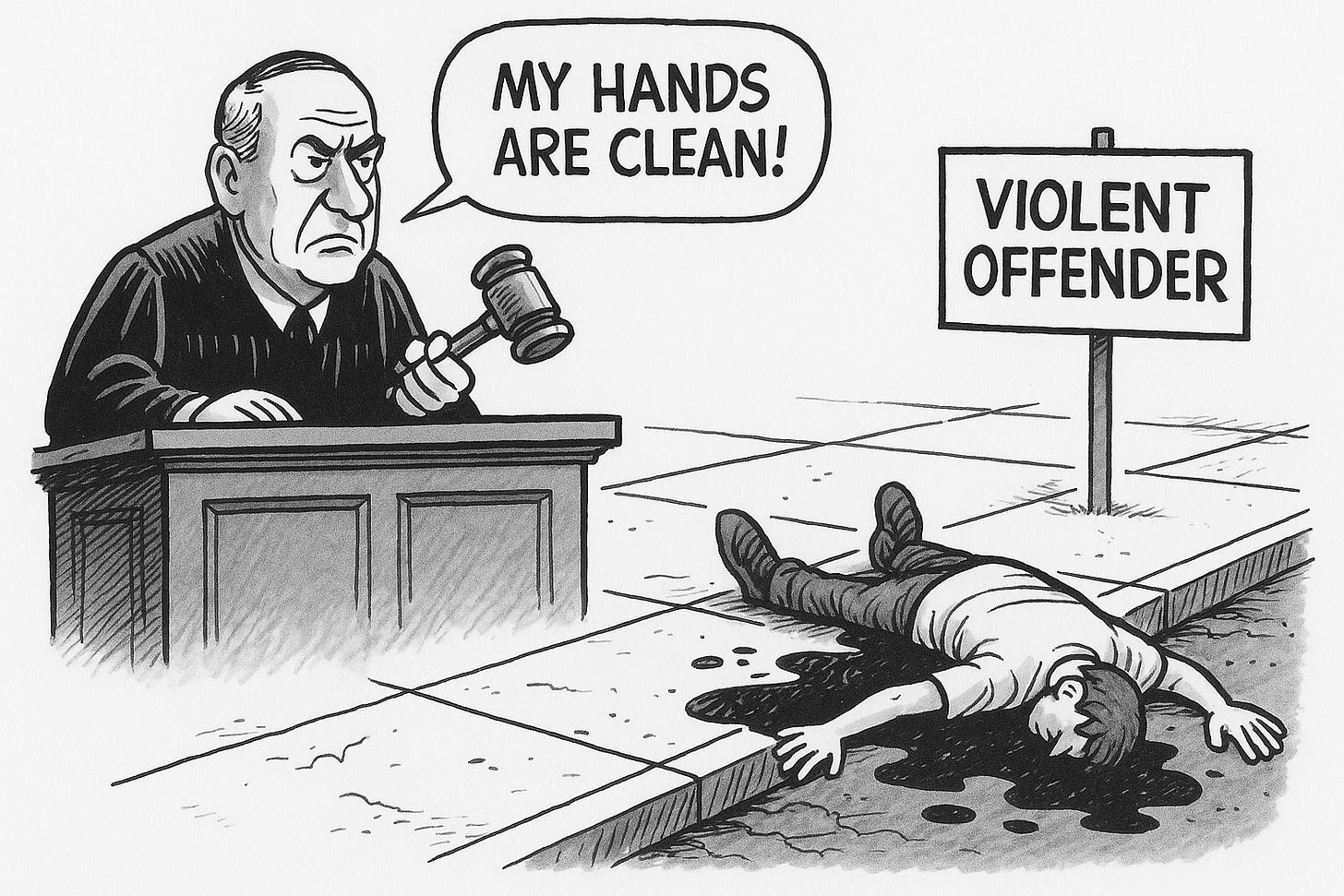

Judgment Without Consequence

why reckless judicial decisions should carry liability

It has long been understood in American law that responsibility does not end at the point of good intentions. A bartender who overserves an obviously intoxicated patron may have meant no harm, yet the law recognizes that his actions—or failures—can unleash consequences that endanger the public. If that drunk patron gets behind the wheel and kills someone, the bartender can be held to account because he played a foreseeable role in enabling the tragedy. We do not excuse the bartender on the grounds that he “hoped” nothing would go wrong. We do not allow him to hide behind the comforting rhetoric of compassion. The law deals with reality, not aspiration.

Strangely, this principle evaporates the moment we step from the bar counter to the courtroom bench.

In jurisdictions across the country, judges routinely release violent offenders with long criminal histories, setting them loose upon an unsuspecting public. When those individuals inevitably commit further crimes—sometimes murder—the judge faces no consequences whatsoever. Not legal consequences, not professional consequences, and often not even the consequence of public scrutiny. While bartenders are expected to grasp the foreseeable risks of overserving alcohol, judges are treated as if they cannot be expected to foresee the risks of releasing someone with ten prior violent felonies and a demonstrated disregard for human life.

The irony would be comical if the costs were not measured in innocent lives.

Modern criminal-justice reformers often speak in the airy language of “equity,” “restorative justice,” and “second chances.” But society is not dealing with abstractions. It is dealing with human beings—both the offenders and their future victims. Thomas Sowell has often reminded us that the first rule of economics—and of public policy—is to ask not what we wish to be true, but what the incentives are, and what the consequences will be. Judges who release dangerous criminals face no downside risk. Their incentives point in only one direction: toward leniency. The costs of that leniency are borne entirely by others.

In economics, this is known as moral hazard—a situation in which one party takes risks because someone else bears the cost. In criminal justice, the moral hazard imposed by judicial immunity is staggering. When a judge releases a violent offender who then murders a store clerk or assaults a mother on her way home from work, the judge pays no price. He will continue receiving his salary, continue enjoying tenure protections, and continue being praised at bar association dinners for his “compassion” and “forward-thinking jurisprudence.”

But the family burying their daughter receives no such insulation.

If bartenders, landlords, truck drivers, and doctors can be held liable for foreseeable harm, why should judges be uniquely exempt? Judicial immunity was created to allow courts to function without fear of personal reprisal from dissatisfied litigants—not to provide a shield for ideologically driven experimentation that endangers the public. The Founders did not imagine a world in which judges would be using their discretionary power to repeatedly release known predators, nor did they believe that public officials ought to be untouchable when their actions produce predictable and lethal outcomes.

A violent criminal with a long, well-documented history is not an unknown quantity. Releasing him onto the streets is not a roll of the dice; it is a nearly guaranteed replay of past behavior. When judges ignore that reality—often for the sake of ideological fashion rather than evidence—they are doing something akin to a bartender watching a staggering patron fumble for his keys and saying, “Well, perhaps this time will be different.”

It is time to reexamine whether absolute judicial immunity is compatible with justice in a world where judicial discretion increasingly substitutes ideology for public safety.

This is not an argument for punishing judges for every crime committed by every defendant they release. But when a judge knowingly disregards clear evidence of danger—when a violent offender with a history of shootings, stabbings, or domestic violence is released without meaningful supervision, electronic monitoring, or bail—it is no longer a matter of hindsight. It is a matter of foresight willfully ignored. And in such cases, the judge’s role is no less causal than the bartender who pours a final shot for someone he knows is about to drive home.

The criminal-justice system already acknowledges the foreseeability of harm. Prosecutors can be held accountable through elections. Police departments can face civil suits. Parole boards can be investigated. The only actor entirely insulated from the consequences of catastrophic decisions is the one who often plays the most decisive role.

If society wants judges to exercise mercy, that mercy must be tethered to prudence. If it wants judges to show compassion, that compassion cannot be selectively allocated to the offender while ignoring the future victim. And if it wants judges to balance risks, then they must bear at least some portion of the consequences when they catastrophically miscalculate those risks in defiance of evidence.

The public has a right to walk down the street without being assaulted by someone who was arrested last week for the very same crime. They have a right not to become collateral damage in someone else’s social experiment. They have a right to expect that the system designed to protect them will not instead expose them to danger.

A society that holds bartenders more accountable than judges has inverted its priorities.

Accountability should not stop at the courtroom steps. If a bartender must answer for the foreseeable consequences of recklessness, then surely those entrusted with life-and-death decisions in the justice system should be held to no less a standard. Innocent lives depend on it.